At 25, Sarah* doesn’t speak to her dad. And she points the finger squarely at him and how he treated her before and after her parents’ divorce.

She knows that people often blame mom when a child doesn’t want to see a father or have a relationship with him, and they accuse the mom of ‘parental alienation.”

“He is the person that alienated himself from me,” she said.

The ‘perfect family’

They looked like the perfect family.

She was her dad’s adventure buddy.

But beneath the image lay a dark truth.

“I felt unsafe,” said Sarah *(whose name along with everyone else’s in this article has been changed for their protection).

Yes, she was the child who was her dad’s canoe partner from a young age.

Yes, she was his biking partner.

Yes, everyone thought they had an enviable father-daughter relationship.

“I felt like it was the only way to get this dad to care about me,” Sarah said.

She remembers biking from St. Paul to Hudson, Wis. when she was in second grade. Her dad Keith knew that her bike was broken but he didn’t take the time to fix it before they left. She rode the entire way with a brake on. “I just suffered through,” she said.

“If we didn’t do what he wanted, there would be hell to pay.

“It was just normal. Either he was blowing up or things were OK.”

‘Walking on eggshells’

She’s still unraveling all the ways her dad’s temper, mood swings, bullying and manipulation affected her. She finds herself unlocking memories sometimes, things she had long forgotten but give her clues about the environment that shaped her.

“Violence is harming another person,” said Sarah. “It doesn’t have to be a physical assault of any kind.”

She added, ”Cultural norms say you can’t hit your wife and kids. So they use other ways to control.”

Being an abuser didn’t fit Keith’s idea of himself. “He would never have labeled himself an abuser,” remarked Sarah. “He did everything else he could up to that line of physically hitting us so that then he couldn’t be an abuser in his mind. It’s intentional that they don’t hit.”

Instead he painted himself as a helpless victim. “He would just say I’m a really sad guy and I’m doing my best and that should be enough for us,” Sarah said. “He would apologize but there was no accountability and he wouldn’t change. He’d say, ‘I’m sorry you felt that way. I’m sorry if I made you feel unsafe.’”

He acknowledged he had a temper, but framed it as being passionate about things. He told them all he was diagnosed bipolar, and used it as an excuse for the rage and depression.

Sarah remembers listening at the laundry chute upstairs to hear what her parents were arguing about in the kitchen. Her mom, Teri, sent her away when they were arguing to try to shield her. But Sarah felt like she would be safer if she knew what they were fighting about.

Then she could adjust her behavior. Then she could try to make her dad happy. Then she could avoid getting yelled at.

Except, she still got yelled at.

That’s how her dad did things.

He didn’t name call or swear. He considered himself a good Christian husband and father. But he made her feel like nothing she did was ever good enough. She was personally deficient.

That message was relentless.

“That has been the most damaging – to feel like you can never be in your own house without putting on a persona. To be walking on eggshells in your own house all the time. It’s a long time to constantly be in fight or flight, reptilian brain,” said Sarah.

‘I ran’

It was her 13th birthday.

They were at her older brother’s soccer game when her dad reached over to touch the necklace on her chest. She told him not to. “He was so pissed at me,” Sarah recalled. He stormed off and left the game.

Back home, he started slamming pots and pans and cabinets in the kitchen as he argued with her mom.

Sarah had been in the basement for about an hour getting ready for her party that afternoon.

She was heading upstairs when she heard something different. This time he swore and called her a derogatory name coupled with a statement that he didn’t care what she thought.

“He had his hand drawn back to hit me,” recalled Sarah. “I ran.”

Five minutes later the first friend showed up for her party. She melted down, but pulled it together by the time the second person showed up.

“I do not remember anything from my birthday party,” she said.

She found out later he had tried to kill himself that night.

This is the incident that Sarah thinks spelled the end of the marriage, although her parents didn’t officially split up for another year.

He had raised his hand against a kid.

Sarah and her brother were among the 14%, or about 10 million children, who experienced some form of maltreatment from a parent or caregiver in the past year (data from FuturesWithoutViolence.org). Sixty percent of children experienced at least one direct or witnessed violent victimization in the previous year.

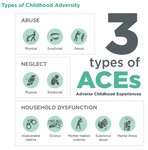

The landmark Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) study launched in 1995 found a significant relationship between childhood experiences of abuse and violence, and a host of negative adult physical and mental health outcomes, including heart disease, stroke, depression, suicide attempts, sexually transmitted diseases, and substance abuse.

‘A pleaser and hyper vigilant’

Sarah has never felt unconditional love from her dad.

“I don’t think he does anything unconditionally,” she remarked.

She recently took an assessment to pinpoint what her biggest saboteur is. What she read finally gave her the words to articulate what she has felt.

“I’m a pleaser and hyper vigilant,” Sarah said, who also struggled with a disabling chronic illness. “The pleaser’s origin story is this: They try to earn attention from helping others. This is an indirect attempt to get their needs met by putting other’s needs above their own. I must give love and affection to get any back. I must earn it and I am not worthy of it.”

She looked up from her phone screen. “This is from you, Keith. That’s my biggest saboteur.”

‘I think he’s narcissistic’

“I’m not sure at what point the reason goes out the window. You can have bipolar and not treat people like garbage,” observed Sarah. “I think he’s narcissistic. That’s much more accurate for him.”

Yes, he has ups and downs, but they occur only when he doesn’t get what he wants.

He’s always right.

Everything in the house was about what he needed. Everyone asked themselves how dad was going to react to something. “That’s how we operated,” said. Sarah. “His volatility was unquestionable. Is he going to be angry and screaming for hours or crying or praying outloud? Who knows. It could be anything.”

The worst times were holidays and events. Car rides were awful. And when they got where they were going, no one ever suspected they weren’t a happy family.

Sarah and her brother didn’t invite friends over but played outside with neighbors instead and went to other people’s houses.

“I’m still dealing with so much of that stuff now. I can’t handle conflict at all. I don’t know what conflict can look like in a healthy environment,” she remarked.

She remembers a therapist in middle school giving them a warning. “The person told my mom she needs to get us away from my dad as soon as possible because he was going to hurt us.”

Shut down by a therapist

Sarah felt relieved when her parents told them they were separating when she was in eighth grade. She had been wishing he would move out for years.

“I remember feeling really guilty for being the thing that kept her tied to him,” said Sarah. “I never felt pressure from her to not like him. I did not feel safe or comfortable around him.”

Her mom brought them to the coffee shop where her dad was a regular. Looking back, Sarah sees that it was a deliberate way to try to control Keith’s behavior. “My mom knew he wasn’t going to cause a scene in his favorite coffee shop.”

Despite their announcement, Keith remained in the house for a long time. Sarah remembers him laying on the couch reading devotionals out loud about being a good husband and father. When they drove somewhere, he blasted love songs and sobbed.

The people around them were surprised when Keith and Teri announced they were getting a divorce, and felt like it came out of nowhere. Keith started making the rounds of their friends, and soon everyone was feeling sorry for him and his struggles. Teri set things straight by laying out the facts that she had been reluctant to tell people before.

At 12 years old, her parents’ marriage therapist asked her what she wanted to have happen if her parents split up. Sarah replied “Just figure it out and stop talking to me. I’m exhausted.”

The therapist turned to her mom and berated her for the “black and white thinking” of her daughter.

“I did not seek therapy for a long time after that. It shut me down,” said Sarah.

‘He’s irrational’

After Keith moved out, he had Sarah over once to bake brownies.

She found out he’d gotten remarried because he posted photos on Facebook.

“It made me feel horrible. He was just lying to me when he said he wants me to be a part of his life,” stated Sarah. “If you’re going to get married and not even telephone me to say what’s happening, you don’t have a leg to stand on.”

He moved out of state, first to one and then another. He’s lived in six in the last 12 years. Keith is a teacher but he can’t keep a job for longer than a few years. When he leaves, he gives his boss a piece of his mind, and always positions himself as an advocate for his students.

One day she was going down the street and saw her dad bike by. She had no idea he was visiting from out-of-state and he didn’t stop to say hello.

It was in that moment that she realized she could never post on social media where she was because he might show up.

“I do not feel comfortable,” said Sarah. “He’s so irrational.”

Another time, they learned he was staying with a friend a block away, but hadn’t reached out.

A year or two ago, her mom was on the phone gardening in her front yard, when Keith and his second wife drove slowly by.

They were all rattled by the sudden appearances. “He’s so creepy,” said Sarah. “He still feels like this is ‘mine.’”

His wife posted an item on Facebook about how children of divorced parents are heartless and manipulative because they pit their parents against each other to get presents.

Sarah sees it differently. Her dad offered to buy her a pair of tennis shoes and pierce her ears one day. Then afterwards, he guilted her into seeing his extended family.

‘You don’t do that to a child’

The custody arrangement required Sarah to spend a month in the summer with her dad out-of-state. She went alone because her older brother was no longer required to go. “It was horrible,” said Sarah. “I wanted to leave every single day. That was the worst our relationship has ever been when I was there. As a dumb 14-year-old that was the closest I ever got to suicide because I felt there was no way out.”

Her dad didn’t spend any time with her, she recalled. “He and his wife would be in their bedroom all day with the door closed. We wouldn’t do anything.”

She had always been a vegetarian and he didn’t make meals she could eat. When they went out to the southern chicken and BBQ joints, there was nothing on the menu without meat.

His wife ripped her iPad and phone out of her hands, and wouldn’t let her talk to friends or even her mom.

“They made me feel like an absolutely terrible person,” said Sarah. “I almost hit his wife when they took away my stuff. I couldn’t control where I was, what I was talking to, or what I was eating.”

Ever since, his wife has told people that Sarah is violent.

His new stepson won an award for an essay he wrote about his amazing stepfather.

Sarah told them she was never going back. Her dad owned $10,000 in back child support at the time, but it was forgiven and she wasn’t required to go again.

Sarah still can’t get over what her dad’s wife did to someone else’s kid.

“You don’t do that to a child,” Sarah said. “How can you not like a kid?”

‘In spite of him’

The last time she spoke to Keith was her junior year of art school. He sent her a text out of the blue. It said: “I’m so depressed today I can’t even move because my daughter is not speaking to me.”

Sarah doesn’t understand why you would send your daughter a text like that.

But for her, it fits into his insistence that he is her father and she needs to respect that by giving him time and attention.

Sarah doesn’t feel the same way. “I get to define what these relationships are,” she said. “I have professors and mentors who have filled that role better than he has.”

She hasn’t seen him in person since her sophomore year of high school.

During her freshman year of college, Sarah thought she was grown up enough to have a healthy relationship with her dad. She called him four or five times. But every conversation centered around him and a project he was embarking on. He wanted her to help him make it work. He didn’t ask about her life at all.

She told him that if he ever wants a relationship with her that he will stop texting or calling until she gets back in touch with him. She told him he needs to respect that boundary.

She’s surprised that he has. “It’s been two years and he hasn’t bothered me.”

She knows if she contacts him, he will feel pride in what she has accomplished. She explained, “It wasn’t because of him. Everything is in spite of him.”

Read more in our Voices Against Violence series here.

• She must have done something wrong

• Assume mothers get custody of the kids in domestic abuse situations? Think again.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here