Dave Christianson of the Minnesota Department of Transportation informed residents that upgrades are being planned for the at-grade crossing on Como Ave., southeast of Lake Como. The crossing has been deemed one of the most dangerous in the state given the large number of people who live within a half-mile of it. (Photo by Tesha M. Christensen)[/caption] By TESHA M. CHRISTENSEN An at-grade railroad crossing in Como has been ranked one of the most dangerous in the state, but plans are being made to change that. The crossing at Como Ave. southeast of Lake Como (next to Minnesota Indian Econ Development at 831 Como Ave.) is the only at-grade crossing that remains in the Twin Cities along this high-speed, high-grade line. There are 50 to 70 trains a day traveling along the line that bisects the Como neighborhood in St. Paul, according to Kathy Hollander of MN350. It’s one of the main lines in the state, and it is carrying seven trains each day of highly flammable crude oil from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota. 3500 people within one-half mile

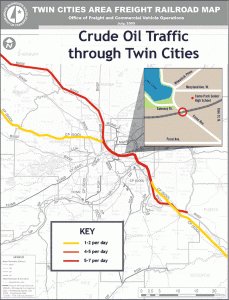

Dave Christianson of the Minnesota Department of Transportation informed residents that upgrades are being planned for the at-grade crossing on Como Ave., southeast of Lake Como. The crossing has been deemed one of the most dangerous in the state given the large number of people who live within a half-mile of it. (Photo by Tesha M. Christensen)[/caption] By TESHA M. CHRISTENSEN An at-grade railroad crossing in Como has been ranked one of the most dangerous in the state, but plans are being made to change that. The crossing at Como Ave. southeast of Lake Como (next to Minnesota Indian Econ Development at 831 Como Ave.) is the only at-grade crossing that remains in the Twin Cities along this high-speed, high-grade line. There are 50 to 70 trains a day traveling along the line that bisects the Como neighborhood in St. Paul, according to Kathy Hollander of MN350. It’s one of the main lines in the state, and it is carrying seven trains each day of highly flammable crude oil from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota. 3500 people within one-half mile  Currently 7 Bakken oil trains, carrying 21 million gallons of Bakken crude, run through the metro each day, and right through Como and Midway. And, the number could rise. (Click map for larger image)[/caption] According to Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) freight and rail planner Dave Christianson, this crossing has “the highest concentration of people around a grade level crossing in Minnesota.” About 3,500 people live within a half-mile radius, according to the U.S. Census. That doesn’t factor in those traveling through on buses, enrolled at one of the three schools in the area (Como Park High School actually borders the track), taking classes at the training center, or enjoying the trails around Lake Como. “Is there anything we can do to get the trains out of the area?” asked a Como resident during the District 10 Community Council Land Use Committee meeting on Feb. 2. “Almost nothing,” replied Christianson. “We’re doing everything we can, but because it is federally regulated we are not the final decider.” A tunnel or bridge? However, the state can work to change the at-grade status at the intersection. Details on what this grade separation will look like, whether it will be a bridge or tunnel, will be made after an engineering study that the city and railroad will complete. It costs $15 a foot to go under and $25 a foot to go over. The crossing is currently protected by four guard gates. There has been one recent accident at the Como crossing, according to Christianson. A driver broke through the gate in front of an oncoming train and was killed. It backed train traffic up for three hours. “The best protection we could put at an at-grade crossing wasn’t enough,” said Christianson. 7 trains carry oil daily In all, 10 trains leave the Bakken oil fields each day. Currently, two travel to the west coast and eight come through Minnesota. Projections before the recent slowdown at the North Dakota oil fields was that those numbers would rise to between 12 and 15 trains a day, but those plans are on hold. Those eight trains enter Minnesota through Moorhead (which is currently working to eliminate all at-grade crossings in its downtown). Then one travels south through Willmar and Pipestone to deliver the crude oil to the Gulf. Of the remaining 7, six are Burlington Northern Sante Fe (BNSF) trains and one is Canadian Pacific (CP). The CP train takes a different route into St. Paul, traveling through Plymouth instead of Anoka, but then hops on the BNSF double-track line that brings it through Como along with BNSF’s six trains that carry about 3 million gallons of crude oil each. Can the trains be rerouted around the Twin Cities? No, according to Christianson. “There are no other thorough tracks left of high quality,” he explained. “All trains come here and leave here.” The cost to construct new tracks ranges from $2 to 5 million a mile. To bypass the Twin Cities, about 60 miles would need to be built at a cost of $120 to $300 million. On top of that would be the cost to hook up the 12 routes that come into the Twin Cities. The risk to residents The most common question Christian receives is: “How much are we at risk?” His answer? There has been one accident in Minnesota in the last two years. There have been five in other places, including the fire that destroyed downtown Lac Megantic in Quebec and claimed 47 lives. The odds are high nothing will happen, “but at the same time there is always that chance and that’s what we’re worried about,” said Christianson. One of the big problems with this type of crude oil is how unstable it is and how hot the fire burns when it erupts.

Currently 7 Bakken oil trains, carrying 21 million gallons of Bakken crude, run through the metro each day, and right through Como and Midway. And, the number could rise. (Click map for larger image)[/caption] According to Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) freight and rail planner Dave Christianson, this crossing has “the highest concentration of people around a grade level crossing in Minnesota.” About 3,500 people live within a half-mile radius, according to the U.S. Census. That doesn’t factor in those traveling through on buses, enrolled at one of the three schools in the area (Como Park High School actually borders the track), taking classes at the training center, or enjoying the trails around Lake Como. “Is there anything we can do to get the trains out of the area?” asked a Como resident during the District 10 Community Council Land Use Committee meeting on Feb. 2. “Almost nothing,” replied Christianson. “We’re doing everything we can, but because it is federally regulated we are not the final decider.” A tunnel or bridge? However, the state can work to change the at-grade status at the intersection. Details on what this grade separation will look like, whether it will be a bridge or tunnel, will be made after an engineering study that the city and railroad will complete. It costs $15 a foot to go under and $25 a foot to go over. The crossing is currently protected by four guard gates. There has been one recent accident at the Como crossing, according to Christianson. A driver broke through the gate in front of an oncoming train and was killed. It backed train traffic up for three hours. “The best protection we could put at an at-grade crossing wasn’t enough,” said Christianson. 7 trains carry oil daily In all, 10 trains leave the Bakken oil fields each day. Currently, two travel to the west coast and eight come through Minnesota. Projections before the recent slowdown at the North Dakota oil fields was that those numbers would rise to between 12 and 15 trains a day, but those plans are on hold. Those eight trains enter Minnesota through Moorhead (which is currently working to eliminate all at-grade crossings in its downtown). Then one travels south through Willmar and Pipestone to deliver the crude oil to the Gulf. Of the remaining 7, six are Burlington Northern Sante Fe (BNSF) trains and one is Canadian Pacific (CP). The CP train takes a different route into St. Paul, traveling through Plymouth instead of Anoka, but then hops on the BNSF double-track line that brings it through Como along with BNSF’s six trains that carry about 3 million gallons of crude oil each. Can the trains be rerouted around the Twin Cities? No, according to Christianson. “There are no other thorough tracks left of high quality,” he explained. “All trains come here and leave here.” The cost to construct new tracks ranges from $2 to 5 million a mile. To bypass the Twin Cities, about 60 miles would need to be built at a cost of $120 to $300 million. On top of that would be the cost to hook up the 12 routes that come into the Twin Cities. The risk to residents The most common question Christian receives is: “How much are we at risk?” His answer? There has been one accident in Minnesota in the last two years. There have been five in other places, including the fire that destroyed downtown Lac Megantic in Quebec and claimed 47 lives. The odds are high nothing will happen, “but at the same time there is always that chance and that’s what we’re worried about,” said Christianson. One of the big problems with this type of crude oil is how unstable it is and how hot the fire burns when it erupts.  Community residents gathered Feb. 2 to learn more about the trains traveling through their neighborhood that carry Bakken crude oil. (Photo by Tesha M. Christensen)[/caption] “The Bakken crude oil is light and extremely volatile,” said Christianson. Treating it is like fighting a tire fire, observed Christianson. Instead of burning out within a few minutes, it takes hours. Emergency personnel handle it by evacuating an area within a half-mile radius of the fires. In comparison, ethanol, which is also transported by rail through St. Paul at the rate of one train a day, has a low flash point. Because of that and its other characteristics, it can be treated with simple water. In the last 15 years of ethanol production in Minnesota, there has not been a single fatality or major injury associated with it. New safety improvements “The railroads are the safest they have been in the last 50 years, yet all you need is one incident and all bets are off,” remarked Christianson. There have been several recent safety improvements. Last year train speed in major cities was reduced from 50 to 40 miles per hour. The federal government is currently working on new guidelines to upgrade all existing tank cars that carry crude oil as they have been deemed insufficient for this use. However, it will take three years to replace the cars once the laws are written. Additionally, as of Apr. 1, North Dakota is requiring that the crude oil go through a gas separator and then be treated so that it is not as flammable to transport. Learn more Mar. 2 The District 10 Land Use Committee will discuss this issue next at its Mar. 2 meeting. Chair Kim Moon anticipates having a discussion with local fire fighters and police to learn more about how ready they are for an emergency at the tracks.

Community residents gathered Feb. 2 to learn more about the trains traveling through their neighborhood that carry Bakken crude oil. (Photo by Tesha M. Christensen)[/caption] “The Bakken crude oil is light and extremely volatile,” said Christianson. Treating it is like fighting a tire fire, observed Christianson. Instead of burning out within a few minutes, it takes hours. Emergency personnel handle it by evacuating an area within a half-mile radius of the fires. In comparison, ethanol, which is also transported by rail through St. Paul at the rate of one train a day, has a low flash point. Because of that and its other characteristics, it can be treated with simple water. In the last 15 years of ethanol production in Minnesota, there has not been a single fatality or major injury associated with it. New safety improvements “The railroads are the safest they have been in the last 50 years, yet all you need is one incident and all bets are off,” remarked Christianson. There have been several recent safety improvements. Last year train speed in major cities was reduced from 50 to 40 miles per hour. The federal government is currently working on new guidelines to upgrade all existing tank cars that carry crude oil as they have been deemed insufficient for this use. However, it will take three years to replace the cars once the laws are written. Additionally, as of Apr. 1, North Dakota is requiring that the crude oil go through a gas separator and then be treated so that it is not as flammable to transport. Learn more Mar. 2 The District 10 Land Use Committee will discuss this issue next at its Mar. 2 meeting. Chair Kim Moon anticipates having a discussion with local fire fighters and police to learn more about how ready they are for an emergency at the tracks. Railroads today

There are currently 4,400 miles of track in Minnesota, down by half from what it once was. Although 80% of hauling in the United States is done by truck, it is more efficient to transport crude oil via rail, pointed out Christianson. Rail offers more flexibility to the refineries on the coasts and the Gulf. The railroads were declining prior to 1980 and so the federal government passed an act that deregulated the railroads. Within 15 years the number of railroads in the country dropped from 60 to seven, and they had returned to profitability, “They basically became land barges,” observed Christianson. It takes 30 to 45 days for a truck to load, get to its destination and return for a new load. A train cuts that down to 12 days. Because trains journey across state lines, they are categorized as interstate commerce and are regulated by the federal government rather than individual states. Three agencies govern the railroads: the Federal Railroad Association (safety), Surface Transportation Board (disputes, mergers, and abandonments), and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. Railroads have the power of eminent domain. As common carriers, they can’t choose what they carry in their cars but must transport whatever they are paid to move.1 in 7 barrels comes from Bakken

The first oil came out of the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota in 2000. Before that the oil was considered unrecoverable, pointed out Christianson. It is now producing 1.2 million barrels a day. One of every seven barrels produced in the United States comes from Bakken. It is the second largest oil field in the U.S. and stretches out over one-quarter of North Dakota. Only one-fifth of the wells have been drilled. While new drilling has slowed down in response to lower crude oil prices in the Middle East, they are still drilling at three-quarter their previous rate. They’re just not finishing the wells, remarked Christianson. This means that if oil prices rise again, they’ll be able to come back online quickly. While some of the crude oil from Bakken is transported via pipeline, it only has capacity for one-third to one-half of production over the next 10 years.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here